The Chavez Ravine acquired its name a little more than a century before the Laws’ legal battle in Willowbrook, with the arrival of Julián and Mario Chavez. In 1844, Julián, a city official, obtained 83 acres of land near the westernmost ridge of what were then called the Stone Quarry Hills. These hills once served as a refuge from flood for members of a local Tongva village, called Yaanga.1 They also contained significant clay deposits, and the three brickyards spread throughout the hills provided the raw material necessary for the construction of the city’s original aqueduct, its Zanja madre (“Mother Ditch”), at the turn of the eighteenth century.2 These brickyards remained a sturdy industry well into the twentieth century, as several Angeleno communities grew among the mustard- and nopal-studded hills.3

This area included four other ravines, later dubbed Sulphur Ravine, Cemetery Ravine, Reservoir Ravine, and Solano Canyon.4 Three distinct neighborhoods—Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop—developed across the Sulphur and Cemetery Ravines, but their histories all fused within the local imagination into one strenuously constructed image of Chavez Ravine.

The hillside communities of the Ravine developed in earnest in 1913, with the relocation of 250 Mexican American families originally housed on the unstable floodplain of the Los Angeles River.5 This movement was subsidized by Marshall Stimson, a lawyer and fixture in local progressive politics who owned much of the land that would become Palo Verde.6 Stimson oversaw a loose real estate network of Ravine plots from his office above the Million Dollar Theater downtown, selling old homes to those willing to repair them and developing a reputation for leniency with his tenants.7

Palo Verde was named for a tree that stood at the fork of Bishops Road, the ravine’s main access route.8 Bishops Road itself branched off of North Broadway, a commercial thoroughfare that featured its own line of the Los Angeles Railway’s “Yellow Cars.”

These streetcars—as well as the Pacific Electric Railway’s “Red Car” lines that bordered the opposite side of the community—connected Ravine residents to the rest of the city, providing the mobility necessary for school, work, and everyday shopping in the years preceding the construction of the Palo Verde School and the neighborhood’s own small network of stores.9

Despite a lack of city services like street paving, lighting, or a reliable sewage system, the three “sub-barrios” of Chavez Ravine gradually blossomed from the late 1920s through the Great Depression.10 The Palo Verde School opened in 1924, followed soon after by a string of community spaces that strengthened ties among neighbors and confirmed their place within the fabric of Los Angeles at large. Palo Verde’s Santo Niño Church was constructed, the Ravine acquired its own bus terminal, and La Loma founded its own small chapel—including a bell wrought by hand by community members—all in the following two decades.11

The family of Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga (b.1897) arrived in Los Angeles just prior to the Ravine’s prime years, and they remained on the same plot of land until the destruction of their neighborhood almost four decades later. Their journey began in 1916, high in the mountains of Zacatecas, Mexico, when Abrana, pregnant with her first child, left her birthplace of Monte Escobedo for America. She settled in Morenci, Arizona with her husband, Nicolas Ybarra, and in 1917 she gave birth to her first daughter, Delphina.12

The Immigration Act of 1917 severely restricted immigration to the United States during this period, but, since most industries in the Southwest depended upon the low-wage labor of Mexican immigrants, mining operations in Arizona were permitted to “sponsor” workers like Manuel Aréchiga. Thus Abrana, recently widowed, and Manuel, both far from their hometown of Monte Escobedo, found themselves in the same copper-mining settlement.13

They fled Arizona’s crumbling copper market in 1922, and settled a plot of land almost six hundred miles west, at 1771 Malvina Avenue in Palo Verde.14 They built their home themselves, like many of their neighbors, and, as the family expanded across three generations, they later constructed another one behind it. Though the Ravine neighborhoods bore a long history of ethnic and racial diversity, at the time of the Aréchigas’ arrival close to eighty-five percent of their working-class neighbors were Mexican or Mexican American.15

This demographic concentration was the result of affordability as well as outright discriminatory housing policy throughout the city. This discrimination received federal support in the mid-to-late 1930s, when New Deal agencies like the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) began administering low-interest private mortgages with small down payments as part of a national campaign to expand home ownership among working-class Americans.16

This program targeted its loan distribution through a hierarchy of “neighborhood risk” that it itself constructed, via a system of local assessments called the City Survey Program. Beginning in 1935, these surveys assigned grades of investment risk to neighborhoods that determined their eligibility for federally insured mortgages and insurance; despite its claims of objectivity, the system prioritized homogeneity, and awarded its highest grades most often to white, Christian neighborhoods. Heterogeneous communities like those of Chavez Ravine, with its sizable Mexican American population, were branded as “hazardous” for such investments solely because of their racial and ethnic makeup.17

This exacerbated existing disinvestment in the area by the city, barring Ravine residents from funds necessary to expand—or even repair—their housing stock. It also set these neighborhoods within the sights of the city’s redevelopment plans. The HOLC used the same assessment methods that redlined neighborhoods like Palo Verde to identify “blighted” areas, which the city then prioritized for demolition.18

As historian and UCLA Emeritus Professor John H.M. Laslett notes—borrowing terms from sociologist Don Parson—two schools of thought dominated the postwar city leadership’s approach to these areas’ neglect. Community modernists, like incumbent Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron, saw “slum clearance” as a prerequisite for the reconstruction of neighborhoods like the Chavez Ravine communities into “balanced residential neighborhoods that would cater to citizens from a wide range of social classes.”19 Empowered by the Housing Act of 1949 and the new resources that it provided for urban redevelopment, Bowron and his allies on the Los Angeles City Council sought to treat a housing shortage and reshape the city through new public housing. The ascendant corporate modernists, meanwhile—supported by the local real estate lobby, the Chamber of Commerce, and Norman Chandler’s Los Angeles Times—desired large-scale “urban renewal” in the service of commercial interests.20

To the residents of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop, these two factions represented liberal and conservative variations on the same threat: the destruction of their homes. This threat materialized in the summer of 1949, with the publication of a book in which Los Angeles City Planning Commission President Robert Alexander selected the three neighborhoods as ideal sites for the construction of a new complex of private and public housing.21 The City Council soon voted unanimously to redevelop the Ravine communities, and, in late 1950, it signed a contract with the Los Angeles City Housing Authority (CHA) for the construction of 10,000 new housing units.22 Robert Alexander joined the design team for the project, and Frank Wilkinson—assistant to CHA head Howard Holtzendorff and the manager of previous CHA projects like Estrada Courts and Aliso Village—became its core public advocate.23

By July 24, 1950, when the Los Angeles City Housing Authority (CHA) informed Chavez Ravine residents of the city’s plan to replace their neighborhoods with a public housing project, at least 1,100 families lived in Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop. Architects Robert Alexander and Richard Neutra designed a complex of churches, schools, recreational facilities, shops, and—despite their resistance to the density it entailedthirteen high-rise apartment buildings. The development was called Elysian Park Heights.24

Wilkinson and other leaders of the Housing Authority assumed that the residents of the area, as impoverished “slum-dwellers”, would welcome what the CHA perceived as a clear improvement in their living conditions. However, residents of the Ravine communities were in fact quite proud of the neighborhoods they’d developed and the homes they’d built by hand.25 The self-made nature of this place was in part a pragmatic response to its abandonment by city leadership, but the steady growth of these communities despite this lack of support also represented a legacy of independence that extended as far back as the Mexican Revolution.26 The displacement of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop residents therefore represented an irrevocable rupture in personal and collective identity, even if this change included promises from the CHA of fair compensation and “first choice” for the proposed housing.27

These promises disintegrated as the actual plan commenced. The Housing Authority began purchasing homes in the three neighborhoods in December 1950, with below-market cash offers. Though a small portion of families accepted these offers outright, the disparity between their payouts and the pricing of unrestricted housing in the rest of the city pushed some into newfound debt. Most residents—the Aréchigas included—were slow to abandon the neighborhoods their families had developed over generations, and this skepticism was affirmed by the announcement that homeowners and families whose main wage-earners were undocumented were ineligible for public housing.28 CHA agents fragmented blocks house by house, with dwindling offers that led the remaining families to scramble for what they feared might be their final offer. As the city increased its pressure on the holdouts, some agents wielded the looming threat of condemnation, and the city’s power of eminent domain, in an attempt to circumvent the buyout process altogether.29

Above: Chavez Ravine property owners protest Elysian Park public housing development, Los Angeles, 1951

On April 26, 1951, many of the residents unwilling to sell their homes attended the City Planning Commission’s hearings on the Elysian Park Heights project. They packed City Hall, homemade placards in hand, and demanded that city leadership recognize their rights as homeowners. The varied targets of the residents’ messages emphasized the complexity of their predicament; many directed their outrage toward the clear destructive force asserted by the city’s eminent domain power, while some focused on public housing advocates like Monsignor Thomas O’Dwyer, an advisor to the CHA’s Wilkinson whose advocacy for the redevelopment project signaled to them a more subtle shade of the same force.30

Agnes Cerda, a Palo Verde resident and founder of the City Center District Improvement Association (CCDIA), delivered powerful testimony on the injustice of her community’s displacement at these hearings. The CCDIA united property owners and tenants from the Ravine neighborhoods into an organized political coalition, and it marshaled much of the local resistance to the early stages of the Elysian Park Heights project.31

An August 1951 Los Angeles Times article, entitled “Settlement Losing Battle for Its Life,” interviewed Ravine residents about their experiences in the wake of the city’s eviction order. The story included interviews with three Palo Verde women central to the community’s resistance—Cerda, Angie Villa, and Abrana Aréchiga. All three rejected the city’s designation of their homes as blighted, and emphasized the lush gardens and open space that distinguished life in the Ravine neighborhoods from the density of the nearby downtown area.32 Despite sustained protests by these families, that same month the City Council approved the demolition of Ravine homes condemned by the CHA, which, a year later, would include the Aréchiga residence at 1771 Malvina Avenue.33

In Laslett’s words:

“The difference, in the eyes of the CHA, was that whereas white settlers from Iowa and Indiana who built their own homes were seen as sturdy pioneers following a time-honored American tradition, Mexicans who did the same thing were seen as breeders of slums.”34

As the last holdouts left the Ravine in search of unrestricted housing elsewhere in the city, the family of Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga remained stalwart. They did not formally appeal the condemnation of their home in 1952, but they still weathered the city’s first wave of demolitions that year.35 Several months later—at the behest of a conservative coalition of business interests and power brokers like the Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler—county residents voted to scrap the public housing project in a referendum on the plan. The CHA continued to file eminent domain suits, as the state Supreme Court ruled that the city council’s housing contract was binding, but aftershocks of this public disavowal resonated throughout local political discourse as the 1953 mayoral election approached.36

Republican Congressman Norris Poulson emerged as the candidate of choice for the Chandler-led consortium of real estate developers and investors, and his campaign sought at every point to label Mayor Bowron’s public housing plans a “collectivist threat to the American free enterprise system.”37 This goal was achieved a little more than a week before the election, in the televised hearings of Michigan Congressman Clare Hoffman’s House Special Subcommittee on Government Operations. In a climactic exchange on May 18, 1953, LAPD Chief William Parker read from an FBI dossier that claimed Frank Wilkinson, the CHA’s chief advocate for the Elysian Park Heights project, was “an active member of the Communist Party, Los Angeles section, for many years.”38 This public allegation further stoked the conservative backlash against Mayor Bowron’s social reform efforts cultivated throughout the previous year by Poulson’s campaign. This reactionary tide swept Poulson and the business elite he represented to victory the following month, and, with public housing cemented as a key manifestation of “creeping socialism,” it sealed the fate of Elysian Park Heights.

In June 1953, Mayor Poulson and CHA leadership—eager to salvage at least a portion of their public housing plans from the new administration’s chopping block—successfully lobbied Congress to “absorb the difference between the money L.A. had already spent from its 1949 contract and the future sale price of the land from Chavez Ravine.”39 Plans for several integrated housing projects, including Elysian Park Heights, were canceled, and in 1954 the city regained possession of the Ravine land. This deal included a stipulation that the reacquired land could only be developed for a “public purpose,” and the next few years included a wide range of failed pitches for the area’s use: “a zoo, an airport, a county jail, a music center, a convention center, a college campus, a golf course, a world’s fair,” and more.40

City leadership did not attempt to return the condemned land to the Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop residents displaced from their neighborhoods for a housing development that did not materialize.41 Instead, key members set in motion a new, not-quite-public purpose for the area—baseball. In late 1955, Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman asked Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley to consider moving his team to Los Angeles, with the backing of Mayor Poulson and County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn.42 The following year, Hahn, once a public-housing proponent himself, hosted O’Malley during a West Coast visit and proposed the former Elysian Park Heights site as a location for a new baseball stadium.43 On October 7, 1957, the City Council, led by Wyman, voted to approve a contract granting O’Malley and his Dodgers organization the 315 acres that comprised Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop in exchange for Wrigley Field, a South Los Angeles stadium he acquired the previous year.44

While the city courted O’Malley and his Dodgers, the Aréchiga family used the cancellation of the Elysian Park Heights project as the basis for a lawsuit against the Los Angeles City Housing Authority. While their attempt to overturn the condemnation of their home stalled in the courts, the community around them emptied further. Palo Verde’s shops and grammar school closed, and yet the family remained in their home.45 A late 1958 decision by the Los Angeles Superior Court strengthened this resolve, as one judge ruled that the city council’s arrangement with the Dodgers—and a public referendum supporting the deal—violated the “public-purpose clause” of the Elysian Park Heights deed.46

One of the only councilmembers to voice concern for the Aréchiga family and the other remaining residents of the Ravine neighborhoods during this legal battle was Edward Roybal. Roybal, the first Mexican-American member of the Los Angeles City Council, denounced the Dodgers deal as well as the original actions of the CHA to force families like the Aréchigas from their home:

“It is not morally or legally right for a governmental agency to condemn private land, take it away from property owners through Eminent Domain proceedings, then turn around and give it to a private person or corporation for private gain.”47

The fate of the holdout families seemed to shift one month later when the California Supreme Court overturned the Superior Court’s ruling that the Dodgers contract was illegal. Opponents of the deal appealed this decision to the United States Supreme Court, but the City Housing Authority seized this momentum to recommence eviction proceedings against the Aréchigas and others.48 In March 1959, the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office ordered the family to leave their homes in thirty days or face a forcible eviction by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.49

The Aréchigas’ suit disputing the CHA’s use of eminent domain collapsed the following October with the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the appeal to the final California court ruling on the Dodgers contract. Roybal convinced the CHA to push the family’s eviction back one more month, in order to prompt a settlement between the family and the city, but no such agreement materialized.50 Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga and their children refused to abandon their property, though, and on May 8, 1959, with reporters from local newspapers and the KTLA television station present, Sheriff’s deputies broke down their door and removed the family and their possessions by force.51

After almost forty years in Palo Verde—including nine years of pressure from the City Housing Authority, Sheriff’s deputies, and even dogcatchers—the Aréchiga home at 1771 Malvina Avenue fell to the city’s bulldozers.52

The family returned to the site later that evening with one large tent and a group of fellow evicted Ravine residents determined to continue the fight against their displacement. Councilman Roybal visited their protest encampment that night to show his support, and the following week he welcomed the residents into city hall to “air their grievances” about the seizure of their land and the brutality of their expulsion from it.53 The Aréchiga family urged the city council to honor the price offered for their property in the city’s own original assessment, but City Attorney Roger Arnebergh responded that this was “not negotiable.”54

Detailed newspaper and television coverage of the Aréchiga family’s forcible eviction energized public support for their predicament, and Roybal continued to criticize the violent methods of the Sheriff’s department. No formal investigation into the actions of city authorities at any stage of the condemnation or eviction processes resulted from this, though, and on May 18 the Aréchiga family packed up their tent and left their former home for the final time.55

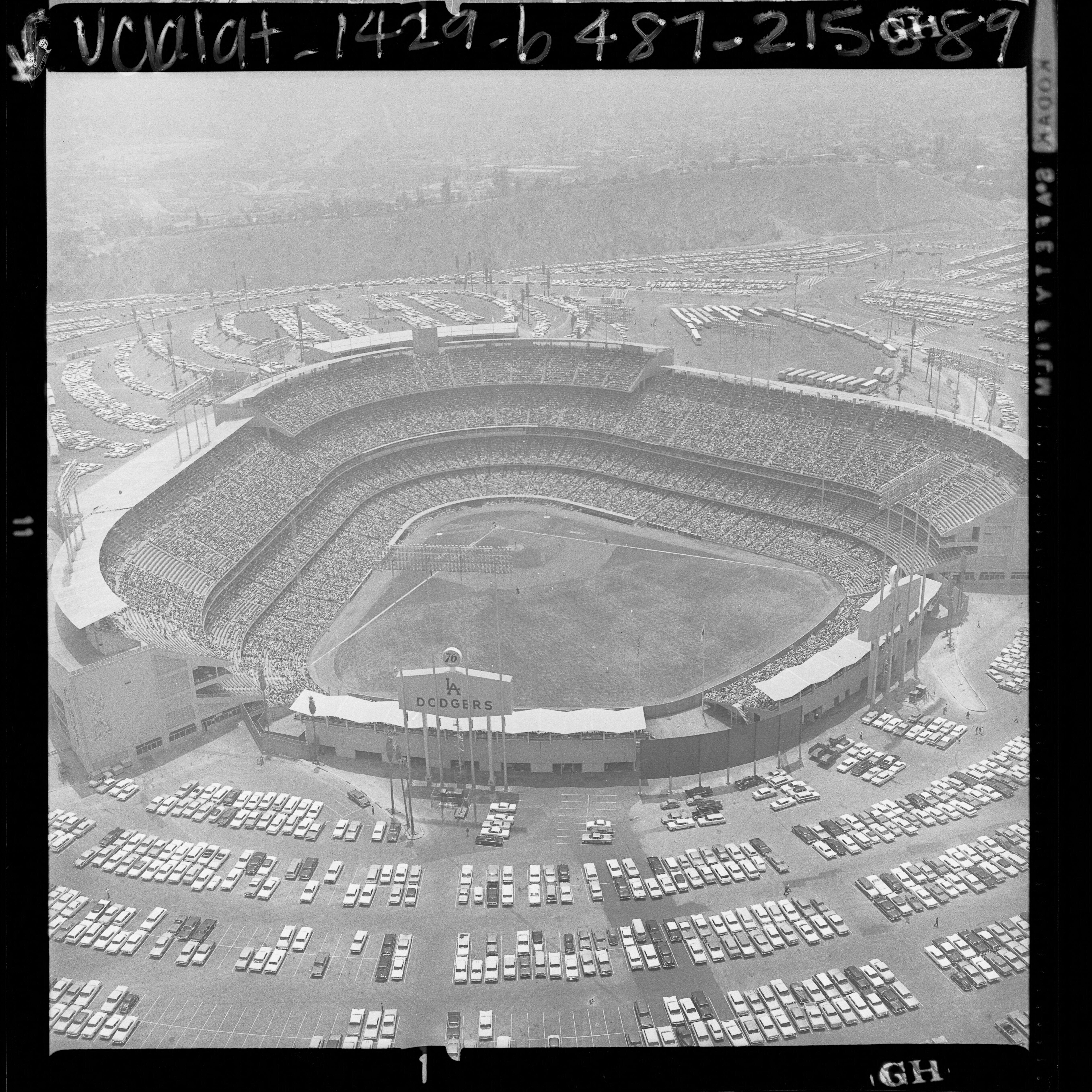

Grading of the land that once held the Palo Verde, Bishop, and La Loma communities began that fall, after the Supreme Court quashed the final appeals of the opponents to the Dodgers deal. The finished park saw its first game in 1962, while Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga rebuilt their lives in City Terrace.56 Both passed away in the early 1970s, but their struggle remained fresh in the minds of Angelenos into the twenty-first century. In 2000, Dodgers President Bob Graziano attended a “reconciliation meeting” in Solano Canyon with surviving residents of the displaced neighborhoods, some of whom found the gesture hollow amid Dodger Stadium’s continued friction with the communities that remain in Chavez Ravine.57

Notes

-

Eric Nusbaum, Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (PublicAffairs, 2020), 15–16. ↩︎

-

“Zanja Madre – Los Angeles State Historic Park,” accessed October 27, 2020, https://lashp.com/history-2/zanja-madre/; John H. M. Laslett, Shameful Victory: The Los Angeles Dodgers, the Red Scare, and the Hidden History of Chavez Ravine (University of Arizona Press, 2015), 29. ↩︎

-

Don Normark, Chávez Ravine: 1949: A Los Angeles Story (Chronicle Books, 2003), 38. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, i–ii. ↩︎

-

Nathan Masters, “Chavez Ravine: Community to Controversial Real Estate,” KCET, September 13, 2012, https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/chavez-ravine-community-to-controversial-real-estate. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, “How Beto Calavera Got His Name.” Vice Sports, 23 March 2020. ↩︎

-

Normark, Chávez Ravine, 32. ↩︎

-

Normak, 37. ↩︎

-

Don Normark, Chávez Ravine: 1949: A Los Angeles Story (Chronicle Books, 2003), 38; Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 82. ↩︎

-

Laslett, Shameful Victory, 16. ↩︎

-

Normark, Chávez Ravine, 28. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 33-36. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 48. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 66. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 84. ↩︎

-

Ryan Reft, “Segregation in the City of Angels: A 1939 Map of Housing Inequality in L.A.,” KCET, November 14, 2017, https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/segregation-in-the-city-of-angels-a-1939-map-of-housing-inequality-in-la. ↩︎

-

Reft. ↩︎

-

Reft. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 56. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 56–57; Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 364. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 245. ↩︎

-

Thomas S. Hines, “Housing, Baseball, and Creeping Socialism: The Battle of Chavez Ravine, Los Angeles, 1949-1959,” Journal of Urban History 8, no. 2 (February 1, 1982): 124, https://doi.org/10.1177/009614428200800201. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 217–18. ↩︎

-

Hines, “Housing, Baseball, and Creeping Socialism,” 132–33. ↩︎

-

Lasltt, 68. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 3, 39. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 66–67. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 67–68. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 71. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 15. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 282–85. ↩︎

-

“Chavez Ravine: A Story of Mexican American Female Resistance in Mid- 20th Century Los Angeles,” The Toro Historical Review (blog), April 28, 2019, https://thetorohistoricalreview.org/2019/04/28/chavez-ravine-a-story-of-mexican-american-female-resistance-in-mid-20th-century-los-angeles/. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 286, 336. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 73. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 336. ↩︎

-

Hines, “Housing, Baseball, and Creeping Socialism,” 139. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 342–44; Laslett, 99. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 353. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 96. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 367. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 119. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 97. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 378. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 336. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 388, 410. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 408. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 111. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 113. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 432. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 432. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 115. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 115. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 117. ↩︎

-

Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 471. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 122. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 3; Nusbaum, Stealing Home, 507. ↩︎

-

Laslett, 130. ↩︎