Racially restrictive covenants were critical to the maintenance of Los Angeles’ discriminatory housing regime, and families who rejected their exclusionary terms therefore played a central role in mid-twentieth-century opposition to this system of racial and ethnic segregation. Henry and Texanna Laws were such a family, and they galvanized local resistance when they occupied their Willowbrook home, just south of Watts, despite the inclusion of a restrictive covenant in its deed.1 Property deeds in Los Angeles and other cities often restricted the sale of property to White Christians. These covenants represented a private agreement among White neighbors, realtors and developers to enforce these restrictions themselves, through lawsuits and intimidation.2 Community members rose up to defend the family, and civil rights attorney Loren Miller and the NAACP successfully challenged the legality of racially restrictive covenants in Supreme Court. The Laws family exemplified how communities successfully resisted residential segregation in the streets and in the courts.

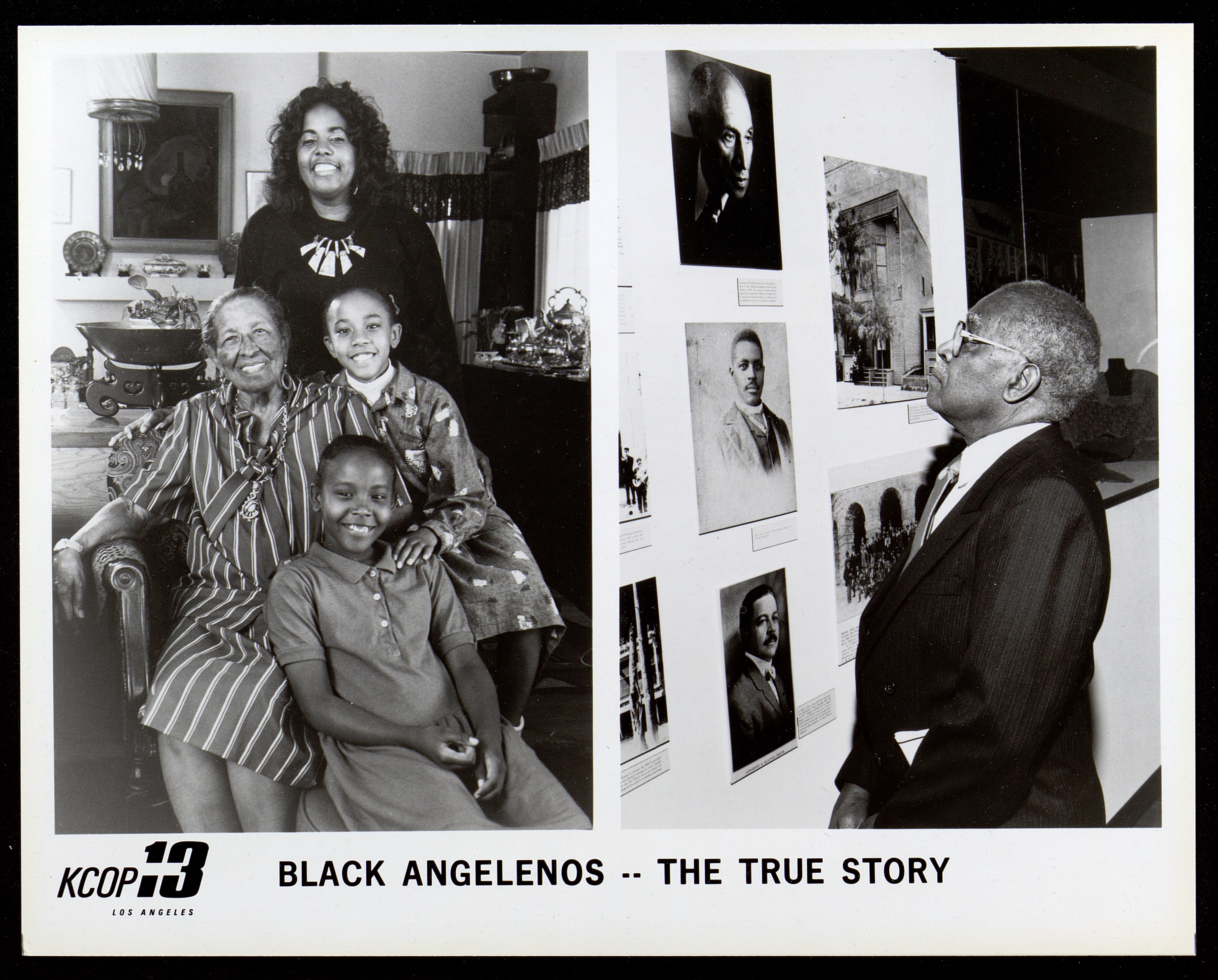

In 1982, journalist Ron Harris argued that the Laws family was a microcosm of the story of Black Los Angeles as a whole. Describing how the life of Anna Laws reflected the larger life of the city, he wrote:

“Anna had seen the celery fields where her children once chased jack-rabbits – in a semi-rural subdivision called Watts – transformed into homes, apartment complexes and businesses. In 1965 she saw those businesses go up in flames. And she saw a city whose racism shut her family out of jobs, housing, and recreation – and that once even jailed her for living in her own home – elect a black mayor. The legacy of her family is that of most of the 505,000 blacks living in Los Angeles – one forged in sweat, suffering, compassion, laughter, tears and sometimes blood.”3

Henry and Texanna Laws purchased property near Watts, on the white side of the de facto racial divider of 92nd Street, in October 1944. The property’s deed included a racially restrictive covenant, a practice used throughout South Angeles to push Jewish, Asian, Latinx and, above all, African-American families into an overcrowded pool of unrestricted housing, with little protection from price gouging and slum-like conditions.4

The realtor managing the sale assured Henry and Texanna that this covenant would not be enforced, but outraged white neighbors did in fact respond with a lawsuit against the Laws. With the help of the NAACP, the Laws resisted the covenant, the neighbors who proposed it, and the city that validated the practice in a legal battle that began in November 1944 and stretched on for the next seven years.5

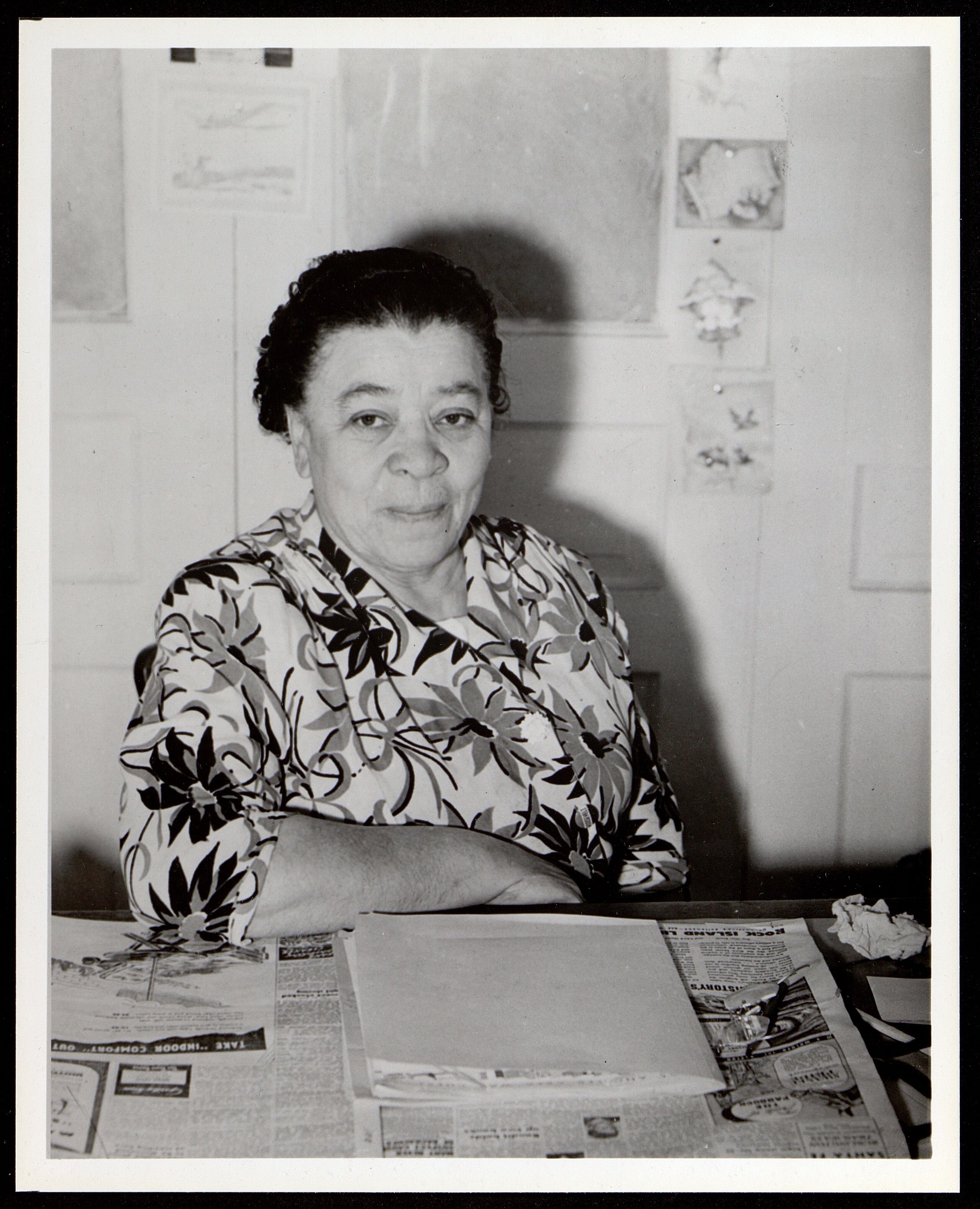

Charlotta Bass, journalist and editor of the California Eagle, led the charge to fight this “92nd Street outrage” through the paper’s coverage and her organization of defense efforts with the Home Protective Association.6

Henry invoked his family’s service during the war in court. Several of the Laws children, including Alfred Laws, were drafted in the mid-1940s and served in the segregated Navy in the South Pacific front. Lifelong civil rights activist and educator Alfred Thomas Quinn, seen here, also served in a segregated Army unit. The struggle for democracy abroad radicalized African American soldiers like Laws and Quinn who demanded civil rights at home.

In a statement emblematic of the “Double V Movement” of the period, which advocated victory against fascism abroad and racism at home, Henry proclaimed to the court:

“The only way they will ever get me out of this house is to shoot me with a Gatling gun and throw my dead body on the other lot. I am a freeborn American citizen. My sons are fighting…in the South Pacific. I buy war bonds. I am working for a defense plant, and so is the rest of my family.”7

Neighbors, friends, and allies rushed to the Laws’ aid and picketed outside their home. Some even formed a food committee to feed the growing protests. Despite this steadfast insistence on defending their home and its purchase, the Laws lost their initial suit. Los Angeles Sheriffs arrested Henry, Anna, and their daughter Pauletta in their own home on November 30, 1945.[8^] Although hostility within Los Angeles imposed extreme duress upon homeowners of color like Henry and Texanna Laws, by the end of the decade national developments would vindicate the family’s struggle.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that courts could not enforce racially restrictive deed covenants, and the covenant governing the Laws’ property was overturned. Civil rights lawyer, judge, Los Angeles Sentinel founder, and future California Eagle publisher Loren Miller argued the case. Five years later he furthered the dismantlement of the restrictive covenant practice by successfully arguing another Supreme Court case, Barrows v. Jackson, which determined that the private citizens who orchestrated such covenants could not sue others for breaching these agreements.8 Dolores Laws recalled, “I was very proud. We felt it was our right to live in it. We felt we would win because we were right.”9

The case lived on in Los Angeles lore, particularly as the issue of fair and affordable housing remained pertinent to African Americans. Opponents of integration stymied the implementation of the Shelley v. Kraemer ruling in their neighborhoods. They circumvented the ruling through both private neighborhood agreements and violent intimidation of African Americans who purchased, or sought to purchase, property in predominantly white areas.10

Norris Poulson was mayor of Los Angeles when the US Commission on Civil Rights visited the city in January of 1960. Despite Poulson’s claims that Los Angeles had an “excellent record in the treatment of minority groups and in the lack of intergroup tension or friction,” Loren Miller gave testimony that “approximately 3,000 of the 125,000 housing units built from 1950 to 1954 in the Los Angeles area were open to non-Caucasian occupancy,” largely in subdivisions developed specifically for Black occupancy. The Los Angeles Urban League found that “less than one percent of new housing between 1950 and 1956 was occupied by minorities.”11 For most Angelenos who were not White Christians, the city’s housing shortage remained in effect.

The Laws family embodied the long struggle against housing segregation in Los Angeles. Despite lawsuits and even arrests, the family refused to accept the legality of racially restrictive covenants and give up their home. Ultimately the Shelley v. Kraemer Supreme Court decision guaranteed the family’s right to their home, but the African American community at large still faced significant obstacles to home ownership. Urban renewal policies and highway construction provided another avenue for residential segregation, but these policies also incited resistance.12

Notes

-

Rasmussen, Cecelia, “Family Stood up to Restrictive Covenants,” Los Angeles Times, December 3, 2006, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-dec-03-me-then3-story.html. ↩︎

-

Freer, Regina, “L.A. Race Woman: Charlotta Bass and the Complexities of Black Political Development in Los Angeles,” American Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2004): 616-17. ↩︎

-

Harris, Ron. “Four Generations: A Family Mirrors Roots of Black L.A.” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Los Angeles, Calif. August 22, 1982, A1. ↩︎

-

Freer, “L.A. Race Woman: Charlotta Bass and the Complexities of Black Political Development in Los Angeles,” 616-17 ↩︎

-

Jessica Garrison, “Living with a Reminder of Segregation,” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 2008, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-jul-27-me-covenant27-story.html; Cecelia Rasmussen, “Family Stood up to Restrictive Covenants,” Los Angeles Times, December 3, 2006, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-dec-03-me-then3-story.html. ↩︎

-

Civil Rights Digital Library. “The Laws Family Await Their Trial, circa 1945, Los Angeles.” Accessed September 14, 2020. http://crdl.usg.edu/export/html/usc/scl/crdl_usc_scl_scl-m0194.html; Freer, Regina. “L.A. Race Woman: Charlotta Bass and the Complexities of Black Political Development in Los Angeles.” American Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2004): 617 ↩︎

-

Harris, Ron. “Four Generations: A Family Mirrors Roots of Black L.A.” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995). Los Angeles, Calif. August 22, 1982, A2. ↩︎

-

“Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953),” Justia Law, accessed January 19, 2021, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/346/249/. ↩︎

-

Harris, Ron. “Four Generations: A Family Mirrors Roots of Black L.A.” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995), Los Angeles, Calif. August 22, 1982, A2. ↩︎

-

Ryan Reft, “How Prop 14 Shaped California’s Racial Covenants,” KCET, September 20, 2017, https://www.kcet.org/shows/city-rising/how-prop-14-shaped-californias-racial-covenants. ↩︎

-

Davis, Mike, and Jon Wiener. Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties. Verso Books, 2020. 12-13. ↩︎

-

Ryan Reft, “How Prop 14 Shaped California’s Racial Covenants,” KCET, September 20, 2017, https://www.kcet.org/shows/city-rising/how-prop-14-shaped-californias-racial-covenants. ↩︎